The $300M Wake-Up Call: Why BioMaterials Need a New Branding Playbook

A strategic analysis of go-to-market models for biomaterials and the limits of traditional ingredient branding.

Part 1: The Ingredient Branding Blueprint

“For today’s biomaterials, sustainability is not the story. It’s not the driver for investment, nor the reason a brand chooses a material. A new material has to function. It has to excite the customer beyond the fact that it’s better for the planet. The story now is: what does biology mean for the future of our products?”

**Part 1 TL;DR:**

Bolt Threads' Mylo secured $300M+ (some sources claim as high as $471 million) in funding and partnerships with Kering, Stella McCartney, Adidas, and Lululemon, then paused production in 2023.

The traditional ingredient branding playbook (the Gore-Tex model) promised that high visibility drives consumer demand - is this the best strategy for biomaterials?

Gore-Tex vs. Mylo: The classic playbook sequenced operational proof before visibility; biomaterials are reversing this, amplifying risk.

Structural Constraints: Biomaterials face four new challenges Gore-Tex never did: radical transparency, performance parity, supply chain volatility, and the aesthetic paradox.

Thesis: Success requires matching visibility to operational readiness, not aspiration.

**Part 2 TL;DR, Teaser:**

While this piece examines ingredient branding for biomaterials, specifically bio-based leather alternatives at a conceptual level, Part 2 will differentiate between categories of biomaterials (mycelium, bacterial cellulose, cell-cultured collagen, and plant-based films) since their manufacturing realities, risk profiles, and branding constraints differ substantially.

Part 2 will also examine how biomaterial brands are navigating these challenges, with some pursuing ingredient branding strategies, others focusing on B2B platform positioning, and still more falling somewhere inbetween, and provide a framework for determining which approach aligns with your material's competitive reality.

“If one were to judge the progress of sustainable fashion by counting press releases about new bio-based materials, the industry would pass with flying colours.”

The $300M Question

$300+ million in funding. Partnerships with Kering, Stella McCartney, Adidas, and Lululemon. More than five years of development. Total output: fewer than 300 commercial units before production paused in 2023 (estimate based on limited-edition releases - detailed terms/volumes are not public). Bolt Threads followed the typical ingredient-branding playbook: secure iconic partners, generate excitement, build consumer pull. Mylo's pause reveals specific structural tensions between ingredient branding's requirements and biomaterials' constraints.

Bolt Threads was an early giant in the field of bio-based leather alternatives. Numerous articles were written about the emerging product, generating excitement over small collaborations that promised a high quality end product which did not compromise on sustainability goals. Everyone wanted to jump in and the brave ones did more than just dip their toes in the water - they committed 100s of millions of dollars to the cause, certain that this investment would pay off with first to market advantage. Press releases abound as Kering, Stella McCartney, Adidas, and Lululemon used their budding relationship with Bolt Threads as a signifier of sustainable business practices. As Tufts Fletcher School professor Kenneth P. Pucker put it, “If one were to judge the progress of sustainable fashion by counting press releases about new bio-based materials, the industry would pass with flying colours.”

The timeline shows a consistent pattern: initial partnership announcements, followed by partner hedging (Kering's VitroLabs investment), then production delays, then pause. Key inflection points: pre-Stella McCartney's March 2021 prototypes, the designer noted the material was “quite stiff” with sheets “not large enough to cut into pants”, and Adidas’ promise of a late 2021 launch. Just five months after Lululemon's limited February 2022 release (only 100 units total across all products), Kering invested $46M in competing technology VitroLabs. The gap between promised delivery dates and production reality became impossible to sustain. (Timeline compiled from company press releases, SEC filings, and reporting by Vogue Business, Business of Fashion, FashionNetwork, Dezeen, Fast Company, and Sourcing Journal, among others.)

Although Bolt Threads’ Mylo was the industry darling, touting partnerships with these greats in the fashion industry, the timeline above reveals the critical gap between public promises and production reality. Despite $300M+ in funding and partnerships with four of fashion's biggest names, Mylo delivered a total output of less than 300 commercial units across five years, and by mid-2023 Mylo production was paused. CEO Dan Widmaier cited macro-economic hardships and claimed that they were “devastatingly close” to reaching the amount of funding needed to scale. (Though the timeline of partner hedging suggests the challenges ran deeper than capital alone.)

Mylo’s rollout executed the consumer-pull half of the ingredient-branding playbook before the B2B readiness half (stable yields, QA, cost control), magnifying risk rather than mitigating it. For technologies still optimizing biological systems, premature visibility doesn't just fail to help, it actively constrains your options by creating public expectations and partner timelines you can't control.

While the sequence (visibility first, scale later) correlates with Mylo’s disappointing outcome, correlation isn’t proof. Bolt Threads’ pause coincided with 2022–2024 cost inflation, investors’ shift toward AI, and the natural risk aversion of luxury partners after Covid-era inventory shocks. Long product-development cycles in apparel and automotive added drag. My claim is narrower: consumer-facing visibility multiplies execution risk when biology-based yields, QA, and unit economics remain unstable. In other words, visibility doesn’t cause failure, it amplifies the impact of underlying volatility.

Biological systems are inherently variable: feedstock consistency, contamination risk, and bioreactor calibration all influence yield variance by double-digit percentages (variables a marketing timeline can’t accelerate). These aren't problems you solve once and replicate; they're ongoing management challenges that require continuous adaptation. Gore-Tex needed to perfect an industrial process. Mylo needed to industrialize biology. That's a much harder problem, and visibility strategies don't account for this fundamental difference. Mylo’s pause may yet prove a temporary inflection rather than a final verdict. But the episode crystallizes structural tensions that any biomaterial pursuing visibility before readiness will face.

Furthermore, if funding was the sole issue, then how did less-funded competitors survive? Some competitors have taken a different approach…whether it proves more successful remains to be seen, but the contrasting philosophy is instructive. Faircraft is pursuing a 'scale quietly, launch late' model: they've prioritized solving industrial supply chain problems, acquired VitroLabs' key patent portfolio, and are conducting rigorous testing with major partners like Balenciaga, Loewe, and Stella McCartney before formal commercial launch. The goal is guaranteeing high-volume material that's structurally and aesthetically indistinguishable from high-end calfskin before creating consumer expectations.

MycoWorks took a similar path, spending years perfecting Fine Mycelium™ before announcing its Hermès partnership, and strategically using cultural platforms (MoMA installations, NYC's 'Freedom of Creation' exhibit) to build credibility without the pressure of immediate commercial delivery. However, even deliberate strategies require adaptation: in October 2025, MycoWorks announced through CEO Matthew Scullin’s LinkedIn post that it would close its South Carolina facility and pivot to sourcing mycelium from cheaper Asian and European producers, focusing instead on its proprietary Rei-Tan™ processing technology. Whether this pivot represents smart strategic evolution or a response to the same scaling pressures that caught Mylo remains to be determined.

Modern Meadow offers perhaps the most instructive example of strategic evolution. After selling its beauty-and-biomedical division in 2024 to focus exclusively on biomaterials, the company developed its Bio-Alloy™ platform and is now launching its leather alternative product, Innovera, with commercial partnerships across different market tiers.

Their partnership portfolio reveals a deliberate segmentation strategy: Mercedes-Benz for luxury automotive interiors (press and prestige) and Bellroy for consumer accessories (volume and proof of scalability). This two-tier approach lets Modern Meadow demonstrate both luxury credibility and commercial viability simultaneously, addressing the dual challenges of performance validation and scaling economics that caught Mylo.

Mexico-based Polybion offers another route to the same end: a bacterial-cellulose platform built on fruit-industry byproducts. By keeping feedstock simple and processes modular, they’ve sidestepped the volatility that plagues fermentation-heavy systems. It’s a reminder that smart process design can be as strategic as brand design. As Polybion aptly puts it, “impact requires scale”.

These companies seem to share a common philosophy: match visibility to readiness rather than aspiration. But none have yet proven that this approach solves the fundamental scaling economics of biomaterials. The real test comes when they attempt to deliver consistent, high-volume material at competitive prices. This logic applies beyond luxury fashion: automotive interiors, footwear and furniture often provide clearer specs, higher volumes and fewer legacy constraints, making them pragmatic early markets for biomaterials innovations. As McKinsey’s State of Fashion 2024 notes, footwear and apparel supply chains are under intense operational and margin pressure, making them spec-driven categories where proven performance and cost predictability consistently outrank narrative appeal in vendor selection. In other words, the market is rewarding proof, not promise… a reality the biomaterials sector must now internalize.

INGREDIENT BRANDING 101: When It Works

Ingredient branding sits at the intersection of B2B proof and B2C pull. The tactic always has two audiences:

Consumer-facing ingredient branding: builds end-customer recognition through hangtags, packaging, and campaigns (think Gore-Tex or Intel Inside).

B2B ingredient branding: builds trust with designers, sourcing teams, and manufacturers. The “brand” shows up in material specs, quality guarantees, and preferred-supplier status, not on the hangtag.

What this means for biomaterials: Most biomaterials need to win B2B first (prove consistency, price, and quality) before a consumer-facing story makes sense. My critique targets visibility that outpaces readiness (the pursuit of consumer pull before B2B proof).

In fashion, footwear, and automotive, new materials are usually adopted through sourcing and compliance programs, not through consumer recognition. Large brands rely on preferred-materials lists and traceability benchmarks to decide which suppliers make it into production pipelines. For example, Textile Exchange reports that over half of all fibres used by major fashion brands are “preferred materials” vetted through such programs. Automotive and footwear companies follow the same logic, emphasizing material qualification, chemical-safety approval, and line-trial performance long before any consumer-facing campaign. For most biomaterials, the early milestones are “passed lab and pilot trials” and “added to brand-approved supplier lists,” not “appeared on a hangtag.” Ignoring this sequence risks misaligning branding strategy with how adoption actually happens in practice.

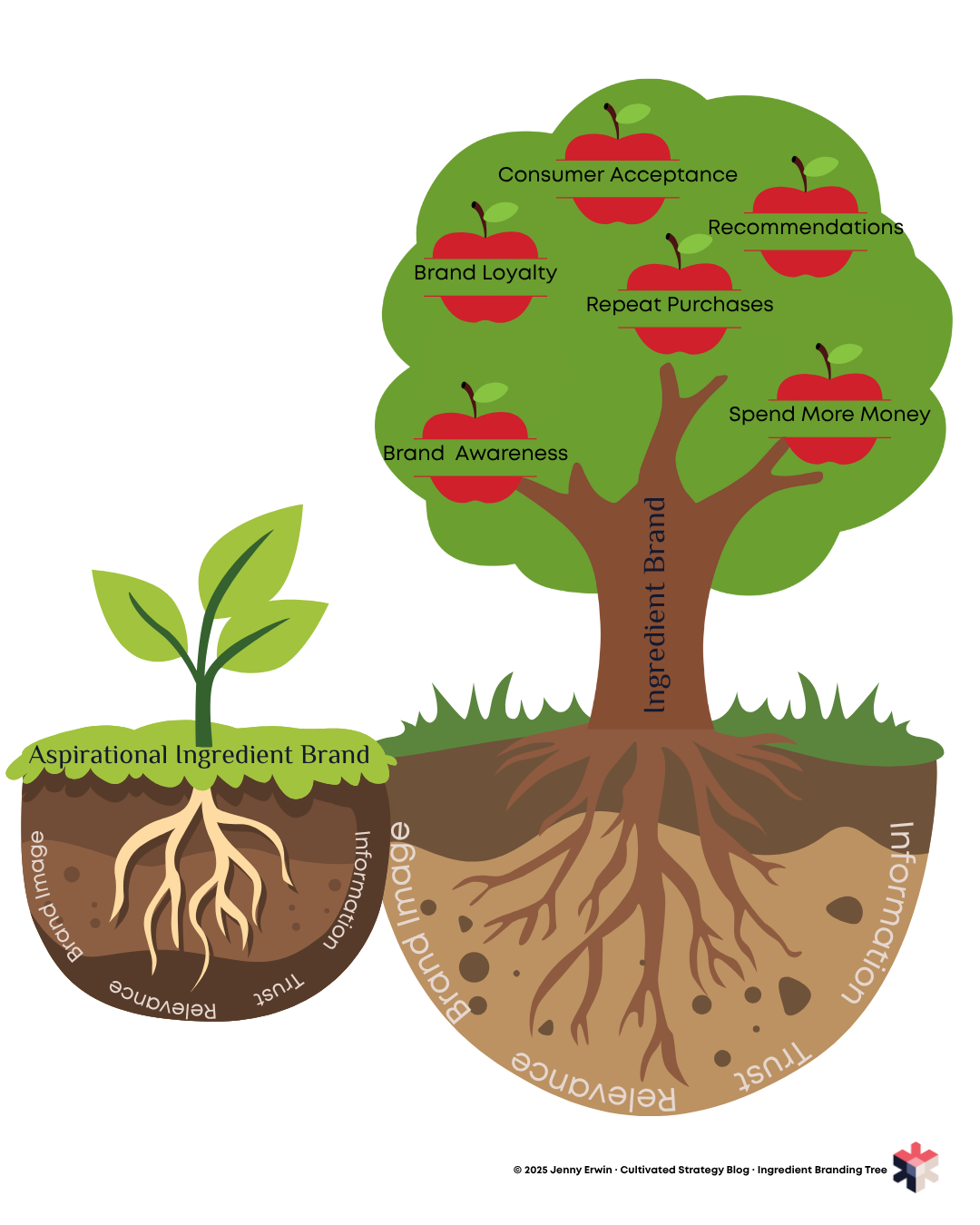

With both modes defined, we can now ask: how does this play out in biomaterials? According to Jochen Lagemann (Managing Director Europe & Asia at Primaloft) and Christian Langer (member of Gore Fabric's Divisional Leadership team), successful ingredient brands require four foundations: information (science-backed transparency), trust (guarantees and quality control), relevance (solving a clear consumer need), and brand image (premium positioning). When these align, ingredient brands achieve premium pricing power, brand loyalty, and repeat purchases.

Not every material supplier qualifies as an ingredient brand. The distinction is whether consumers recognize and request your material by name. The question for biomaterials: can they achieve consumer recognition when their core value proposition, sustainability, does not impact the material’s performance and is often invisible?

The Classic Success Story:

Gore-Tex (1976)

When Gore-Tex launched in 1976, it solved a problem the outdoor industry had failed to crack for decades: a fabric that was simultaneously waterproof and breathable. This breakthrough gave Gore unprecedented leverage to dictate terms. They mandated certified manufacturing partners, required visible co-branding on every garment, and demanded point-of-sale educational materials. The company built an obsessively controlled quality system and backed it with an unconditional guarantee: "GUARANTEED TO KEEP YOU DRY." Early adoption by NASA (1981 Columbia mission) and the U.S. Military (40+ years of continuous use) provided instant credibility with performance-obsessed consumers. The result, true consumer insistence, was something vanishingly rare in materials.

By the mid-2010s, Gore-Tex's brand equity was so powerful that it transcended technical performance entirely. Between 2014 and 2018, the membrane experienced a cultural renaissance. High-fashion houses like Prada (whose Prada Sport line had featured Gore-Tex since the late 1990s) continued collaborations, while streetwear powerhouses like Supreme began releasing standalone Gore-Tex pieces with highly visible branding. The peak came in 2017-2018, when Virgil Abloh's Off-White FW18 "Business Casual" collection featured Gore-Tex tracksuits and Supreme's FW18 season launched Gore-Tex as a fashion statement rather than functional gear. A performance membrane had become a luxury status symbol.

Gore-Tex's path wasn't frictionless. Just two years after launch, the company halted production and recalled millions of dollars in product due to leakage complaints, implementing stricter design standards before relaunching. Decades later, Greenpeace's Detox campaign forced costly reformulation away from PFAS compounds. But these challenges arrived sequentially —> performance skepticism in the late 1970s, environmental scrutiny in the 2010s. That's three decades to build capital reserves, brand equity, and market dominance before sustainability became a consumer expectation. Biomaterials enjoy no such grace period. They must be both technically flawless and ethically transparent from day one, while competing against existing materials whose empires were built before anyone cared about their chemical footprint.

The Gore-Tex playbook demonstrates the four pillars that define ingredient branding success: Information (integrated communication across the value chain, science-backed transparency), Trust (unconditional guarantees, elite proof-of-concept from NASA and military use, obsessive quality control), Relevance (solving a critical unmet need with no viable alternatives), and Brand Image (premium specialist positioning that evolved to include sustainability). When these foundations align, they create consumer pull, premium pricing power, brand loyalty, and repeat purchases. However, Gore-Tex operated under conditions that no longer exist. The biomaterial era demands the same outcomes under fundamentally different constraints.

Four Challenges gore-tex didn’t face

(Note: Biomaterials aren’t a single category. Mycelium, bacterial cellulose, cell-cultured collagen, and plant-based films each have distinct scaling hurdles, cost curves, and risk profiles. The following challenges apply broadly at the branding level. In Part 2, I’ll map how each category’s manufacturing reality shifts its branding options.)

Problem 1: The Burden of Radical Transparency and Scrutiny

Gore-Tex's Advantage: Gore-Tex launched in an era where consumers and regulators focused overwhelmingly on performance. Its proprietary material (ePTFE, a PFAS compound) was accepted as a scientific breakthrough, and its long-term environmental and chemical impact was not a primary consumer concern until decades after launch.

The Biomaterial Challenge: Biomaterials are inherently judged by their virtue, meaning they must achieve radical transparency from day one. They are immediately scrutinized for sourcing, land use, chemical processing (even if bio-based), and true end-of-life cycle (e.g., "Does it really compost?"). This exponentially increases the burden of proof and exposes the brand to the risk of greenwashing claims if communication is not flawless. This complexity is significantly higher than simply promising to keep the user dry.

Empirical Support: A 2024 USDA-sponsored report on the bio-based products industry flagged traceability and feedstock disclosure as major obstacles in commercialization.

Problem 2: Performance Parity vs. Performance Breakthrough

Gore-Tex's Advantage: The original Gore-Tex was a category-defining breakthrough (waterproof and breathable) that solved a previously unmet, critical consumer need. It had no viable competitors and could quickly dictate market requirements.

The Biomaterial Challenge: Most biomaterials today compete on parity EITHER with cheap, scalable, and entrenched synthetic materials (polyester, conventional nylon, conventional cotton), OR heritage products such as bovine leather. They often enter the market at a higher cost with questionable scaling limits and unproven durability claims. The ingredient brand must convince manufacturers and consumers not only that it is better for the planet, but that it is equally or more effective than the proven (and often cheaper) legacy solution. This is a dual challenge that Gore-Tex never faced. Furthermore, unlike Gore-Tex, where breakthrough performance was the primary objective, bio-leather's performance parity benefits (e.g., durability, hand-feel) are often only pursued as necessary requirements to match the incumbent, not as a unique, category-defining advantage.

Empirical Support: Even bullish industry roadmaps classify most next-gen materials as early commercialization/development and say they require further technological advancement before wide adoption. In parallel, consumer data shows quality/price/value outranks sustainability in purchase criteria, even among “early adopters,” which means unproven parity and/or performance will neutralize any sustainability halo at the point of sale.

Problem 3: Supply Chain Volatility and Scaling Risk

Gore-Tex's Advantage: Gore-Tex is based on a proprietary chemical engineering process (stretching PTFE). This allowed for centralized quality control, consistent production, and predictable cost management once scaled.

The Biomaterial Challenge: Biomaterials often rely on complex or volatile inputs: agricultural feedstocks, specific waste streams, or energy-intensive fermentation/bio-engineering processes. This leads to extreme supply chain complexity and cost volatility. Achieving the massive scale required to appeal to host brands is a major risk, as quality control can vary wildly based on biological factors, leading to unpredictable quality and cost for the final product. To be fair, some inputs are inherently easier to standardize than others. But the basic challenge holds: biology is variable, and consistency costs money.

Empirical Support: A 2024 industry survey of vegan bio-leather technologies found that many firms ranked “scalable fermentation/bioreactor yield” and “feedstock variability” among their top three barriers to commercialization.

Problem 4: The Aesthetic Paradox

Gore-Tex's Advantage: Gore-Tex created a completely new performance category, making the material's name mandatory for communicating the product's function (e.g., "waterproof breathable jacket"). The ingredient was the feature and the benefit.

The Biomaterial Challenge: Most bio-leather alternatives are designed to replicate the aesthetics and tactile feel of a known, heritage product (traditional leather), which has a wide variety of use cases. While successful mimicry is an operational goal, it creates a severe brand cue deficit. Unlike Gore-Tex, where the membrane and guaranteed function serve as a verifiable feature visible not only on the garment's hangtag but also in its performance, the biomaterial's core value of ethical sourcing and sustainability is invisible, intangible, and non-performative at the point of sale. Successful replication of traditional leather erases any visual or tactile signal the ingredient brand needs to generate consumer pull.

Empirical Support: Designers working hands-on with MycoWork’s mycelium derived next-gen leather have reported near-indistinguishability (“…my seamstresses couldn’t tell…”) with traditional leather. In a controlled choice test where price and quality were held constant, 60% of sampled U.S. consumers selected next-gen leather, driven primarily by environmental and animal-welfare motives, benefits not visible in the product’s look/feel. However, in this controlled choice test, consumers were made aware of the environmental and animal-welfare benefits. They would not have the same experience with a physical product. Absent a cue, the ingredient’s value is easy to miss.

Separate operational vs. strategic failure

The Core Question: Strategy vs. Timing

These four challenges raise a fundamental question: Is ingredient branding inherently incompatible with biomaterials, or did Mylo and others simply pursue it too early?

There are two possible interpretations:

Interpretation 1: Strategic Mismatch. Ingredient branding requires consumer recognition of a performance breakthrough (Gore-Tex's waterproof breathability, Intel's processing speed). Biomaterials offer an ethical breakthrough (sustainability) that consumers can't see, feel, or directly experience. The visibility that drives ingredient branding success paradoxically undermines biomaterials by creating performance expectations before production systems can deliver consistency. The strategy itself is wrong for the category.

Interpretation 2: Execution Timing. Ingredient branding can work for biomaterials, but only after they achieve true performance parity and production stability. Mylo's mistake wasn't pursuing ingredient branding. It was pursuing it before solving the operational fundamentals. Companies that build partnerships after proving they can deliver consistent material at competitive costs may still succeed with traditional ingredient branding approaches.

These two interpretations aren’t mutually exclusive. They form a spectrum. Some biomaterials face a genuine strategic mismatch; others simply mistimed visibility. Most companies fall somewhere between these poles, adjusting tactics as technical maturity evolves. This distinction matters because it determines what biomaterial companies should do next. If ingredient branding is fundamentally incompatible (Interpretation 1), then companies should abandon consumer-facing strategies entirely and focus on B2B platform positioning. If it's purely a timing issue (Interpretation 2), then companies should delay visibility until operational readiness, but can still pursue the same ultimate goal.

The four challenges outlined in the “Four Challenges Gore-Tex Didn’t Face” section above indicate genuine structural incompatibilities, biomaterials face constraints Gore-Tex never encountered. They prove that the traditional playbook needs fundamental adaptation, not that ingredient branding can never work for biomaterials. Success requires either: (a) achieving such dramatic performance breakthroughs that sustainability becomes secondary to function, making the material visible for what it does rather than what it represents, or (b) developing entirely new approaches to building brand equity when the core value is invisible. Some firms will argue that early storytelling was essential to raise the capital that kept their R&D alive. Viewed through that lens, visibility functioned as a necessary bridge. It was a short-term financing tool that bought time for R&D, even as it constrained long-term strategy.

Part 2 will examine which biomaterial companies are pursuing which paths, and provide a framework for determining which approach aligns with your material's competitive reality.

“Biomaterials are inherently judged by their virtue, meaning they must achieve radical transparency from day one.”

The Challenge Multipliers: Trade, Tariffs, and Transparency

1. Regulatory Multiplier: EU Digital Product Passport (DPP)

The core thesis of the biomaterials sector, that invisible ethical virtue will eventually translate into competitive value, is being tested by new law. The EU Digital Product Passport (DPP), mandated under the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), will require textile and footwear products placed on the EU market to carry a permanent, machine-readable digital record of their composition, environmental performance, and durability. This mandate is set for phased rollout.

The DPP effectively transforms a voluntary ethical claim into a non-negotiable compliance requirement.

Verifying Volatility: The DPP mandates specific, verifiable data on Lifecycle Assessment and material composition. For volatile biological systems, this mandatory disclosure of environmental footprint and material origin directly tests the consistency and scalability claims that led to Problem 3 (Scaling Volatility). Any feedstock inconsistency or batch-to-batch variation is no longer a mere production hiccup, but a verifiable compliance failure.

Forcing B2B Maturity: Companies must now invest in high-cost, verifiable data infrastructure, tracing inputs across multiple tiers of the supply chain, before they can even think about consumer branding. This fundamentally reinforces the core strategic truth: operational proof (DPP-readiness) must now precede consumer-facing visibility.

2. Geopolitical Multiplier: U.S. Tariffs and Sourcing Dependencies

Beyond regulatory complexity, biomaterials relying on complex globalized supply chains are acutely exposed to increasing geopolitical friction, particularly concerning U.S. tariff volatility and trade relationships with key manufacturing hubs in Asia.

Cost-Parity: Historically, textile producers have relied heavily on countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, and China to achieve necessary cost economies. However, U.S. tariffs have recently been applied to imports from these very countries, with some apparel and footwear tariffs increasing dramatically.

A Moving Target: This volatility risks neutralizing the cost-advantages of scaling offshore, making Problem 2 (Cost Parity) a constant, moving target. If a biomaterial producer achieves cost parity with traditional leather in a country subject to a sudden 46% U.S. tariff increase, that parity vanishes instantly, destroying unit economics and margin stability.

Localization Mandate: This friction demands that biomaterial companies either absorb massive cost increases or accelerate localization strategies (e.g., using regional feedstocks and manufacturing). Sourcing and manufacturing are no longer purely business decisions; they are geopolitical de-risking strategies.

“The core thesis of the biomaterials sector, that invisible ethical virtue will eventually translate into competitive value, is being tested by new law.”

Consumer Perception: The intent-behavior gap

Consumer sustainability data presents a paradox. PwC's 2024 Voice of the Consumer Survey (20,000+ consumers across 31 countries) found 80% claim willingness to pay premiums for sustainable goods, with average tolerance of 9.7%. Among Millennials, 73% report willingness to pay extra for environmentally sustainable products.

But stated intentions don't predict luxury-tier behavior. A 2025 study of affluent German luxury consumers (Future Business Journal) found that sustainability is not a primary purchase factor for luxury goods, and these consumers won't pay premiums specifically for sustainability. At the luxury tier, performance, heritage, and exclusivity remain the primary drivers. Sustainability functions as a value-add, not a value driver.

My own primary research for my master’s thesis on the adoption of bio-based leather alternatives, which included 139 equestrians (college-educated, $125K-$500K+ income, investing $3K-$10K in custom leather saddles), corroborates this luxury-specific pattern. While 52.9% associated alternative leather with environmental benefits and 50% with animal welfare, the intent-behavior gap was stark: 74.3% would not pay a premium for bio-leather even when assured of performance parity. Respondents emphasized that materials must match or exceed traditional leather in durability (92.1% rated essential) and quality (90.7%) before sustainability becomes relevant. As one participant noted: "It would have to be as supple, elegant, and comfortable as my [$8,000 custom jumping saddle]. The problem I see with synthetic leathers are the lack of comfort and adjustability." Although equestrian saddlery may seem niche, it’s one of the most demanding real-world tests for leather performance: high abrasion, outdoor exposure, load-bearing stress, and an expectation of durability and usefulness over at least a decade. If a bio-based leather can meet those standards, it can credibly compete in any luxury-performance category.

The critical insight isn't that consumers don't care about sustainability, it's that luxury consumers prioritize differently. Mass-market consumers may make sustainability-driven trade-offs on price or performance. Luxury consumers won't. For biomaterials targeting luxury applications (Hermès bags, automotive interiors, high-end fashion), the burden of proof is absolute: match or exceed incumbent materials on every performance dimension first, then sustainability becomes a differentiator. Consumer pull, the foundation of ingredient branding, exists only after performance parity is proven, not before.

Modern Meadow's dual-partnership strategy with Mercedes and Bellroy suggests one possible path forward: pursue luxury partnerships for brand validation and performance proving grounds, while building actual volume through accessible consumer goods categories where sustainability-conscious consumers exist in sufficient numbers and price tolerance is higher. The Mercedes partnership signals 'our material meets luxury standards.' The Bellroy partnership signals 'we can actually deliver at commercial scale.' This bifurcated approach acknowledges that luxury consumer pull may be insufficient on its own, but luxury validation remains valuable for building credibility across market segments.

“Mass-market consumers may make sustainability-driven trade-offs on price or performance. Luxury consumers won’t.”

The VC Pathology: When Fundraising Strategy Undermines Commercialization

Before concluding that the traditional ingredient branding playbook needs fundamental adaptation for biomaterials, we should examine why so many companies pursued high-visibility strategies despite obvious operational unreadiness. A simpler explanation may be at play: ingredient branding is optimal for fundraising even when it's premature for commercialization.

The Gore-Tex story is legible to VCs and corporate partners. It demonstrates a clear path from material innovation to brand equity to premium pricing. Luxury brand partnerships provide validation that unlock subsequent funding rounds, even if those partnerships never reach commercial scale. Those logos on a pitch deck are worth millions in credibility, regardless of unit volume delivered.

This creates an inherent pathology within the sector: the optimal strategy for securing venture capital (high-profile, consumer-facing partnerships) is inherently suboptimal and premature for near-term commercialization. Those high-profile logos may be a fundraising currency, but they impose a crippling execution risk and unrealistic timelines on a nascent, biologically volatile supply chain.

An insider might argue that a responsible leadership team should not allow the urgent need for capital to dictate a commercial timeline that risks a $300M+ failure, thereby damaging the credibility of the entire biomaterials category. That said, if the primary goal is surviving long enough to solve technical challenges, then premature visibility might be a perfectly rational bet, even if it ultimately creates constraints you must later navigate. Early visibility isn’t always naïve. In capital-intensive platform plays, controlled visibility can be a deliberate financing tool to recruit partners and unlock funding. The pathology arises only when that visibility becomes the operating plan rather than the bridge to readiness.

This doesn't invalidate the four challenges outlined above. It simply clarifies the question: biomaterial companies aren't choosing between 'ingredient branding works' or 'ingredient branding doesn't work.' They're navigating when to deploy visibility, how to sequence partnerships and production readiness, and whether consumer pull is necessary before achieving operational stability or can be built afterward. The answer likely varies by material, application, and competitive positioning…which is why a framework for making these decisions becomes essential.

To sum it all up…

The success of Gore-Tex provides the essential blueprint for ingredient branding: a non-negotiable focus on trust, quality dictation, and the functional relevance of a product that represents a technological breakthrough. The ultimate goal, consumer insistence, was achieved by leveraging a clear, verifiable performance advantage (waterproof breathability) to dictate branding requirements and justify a significant premium. However, as new material innovations increasingly focus on invisible virtue (sustainability) or parity (mimicking heritage products) rather than purely disruptive function, the foundational rules that guided Gore-Tex's rise may now prove incomplete for navigating the modern market.

The Mylo story must serve as a terminal diagnosis for the VC-driven pathology of premature commercialization. The sector cannot afford another failure where the optimal fundraising strategy actively undermines credible commercial viability. Consequently, success now requires one of two things: either achieving a genuine performance breakthrough that makes the material functionally non-negotiable, or developing a radical new approach to translating invisible virtue (sustainability) into compelling consumer value. Part 2 will shift from critique to construction, offering a strategic framework for sequencing production readiness and brand visibility to navigate this high-stakes choice.

Note: This analysis focuses on go-to-market strategy, not bio-process engineering.

About the author

Jenny Erwin is a strategic marketing consultant specializing in sustainable materials and luxury brand positioning. Her master's thesis explored go-to-market strategies for cell-cultured leather in the equestrian luxury saddle market, including primary consumer research with 139 equestrians, and comprehensive competitive analysis of biomaterial technologies. She holds a BFA in Advertising and an MA in Luxury and Brand Marketing (Summa Cum Laude) from SCAD, and previously founded sustainable fashion brand Apacceli, which launched at the 2018 World Equestrian Games, showed collections at New York and Paris Fashion Weeks, and was invited to collaborate with Macy’s on a 2019 collection for their Market at Macy’s initiative. Jenny is currently exploring opportunities in strategic marketing and commercialization for next-generation materials. Click here to connect on LinkedIn.

What's Next: Part 2 will provide a framework for determining which branding strategy works best for your material.

In the meantime: Which of these four challenges resonates most with your experience scaling biomaterials? I'd love to hear from practitioners navigating these tensions. Click on this link to go to my LinkedIn post on the topic and tell me your thoughts.

The elephant in the room: Manufacturing is the harder problem. You can't brand your way out of inconsistent yield rates or a 40% defect problem. I know this. The supply chain experts reading this know I know this. But here's the thing - the technical and strategic challenges aren't sequential. They're parallel. The companies that win will excel at both. But that doesn't mean we can't rigorously examine each on its own terms.